Key Takeaways

- Use dataflows instead of Power Query in semantic models when you want re-usable, governed Power Query transformations outside individual semantic models, especially when the same transformation logic would otherwise be duplicated and could drift over time.

- Gen1 works in Pro workspaces but useful capabilities like incremental refresh, computed/linked entities and DirectQuery require Premium or PPU capacity. Gen2 requires a Fabric capacity, but gives you better lifecycle automation, more re-usability across the variety of destinations you can write to (lakehouse, SharePoint, etc.), and a better user experience with autosave and background validation.

- Dataflows are strong for low-code ingestion, transformation and writing to a variety of data storage destinations in the case of Gen2. Notebooks are generally more cost-effective from a CU perspective and still win for large-scale or custom requirements (i.e. complex Spark logic, libraries, testing), at the cost of more engineering overhead. Data Wrangler in notebooks provides a GUI similar to Power Query's to pick code snippets for common transformations, and Copilot to assist with writing code.

This summary is produced by the author, and not by AI.

In this article, we'll discuss briefly what dataflows are, how Gen1 and Gen2 are different, which new updates are interesting, and which advantages dataflows have over Power Query in import semantic models and Fabric notebooks.

Intro to Dataflows

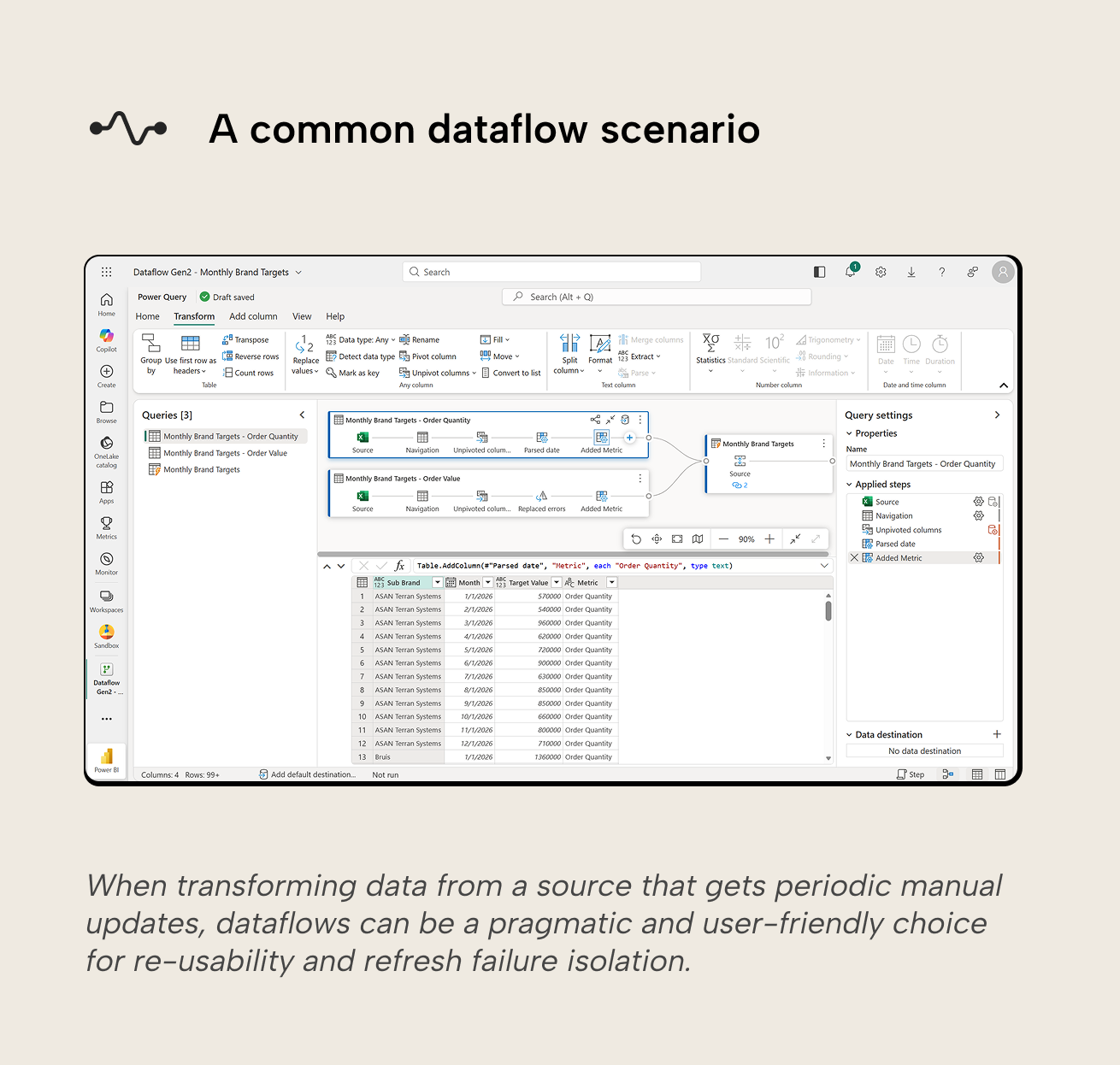

Dataflows are re-usable low-code data transformation items in Power BI (Dataflow Gen1) and Microsoft Fabric (Dataflow Gen2). They connect to data sources, perform transformations defined in Power Query M and persist the resulting tables. Think of them as the Power Query layer moved out of an import semantic model, so the Power Query transformations can be re-used and governed independently from the semantic model.

Some common dataflows use cases include:

- Centralizing repeated data transformations by decoupling them from semantic models.

- Moving data from a variety of sources to a variety of Fabric and Azure destinations.

- Exposing data from a source that users shouldn’t directly interact with, or just in a format that's more suitable for the user.

In practice, dataflows sit in the sweet spot between Power Query embedded in individual semantic models (fast to build but hard to re-use and govern) and full data engineering pipelines or notebooks (most flexible but more overhead).

The following diagram helps you to understand where dataflows fit into the “big picture” of Fabric and Power BI.

Gen1 and Gen2

Dataflows have been around for a while. Since the introduction of Microsoft Fabric, 2 generations exist in parallel: Dataflow Gen1 (“Gen1”) and Dataflow Gen2 (“Gen2”). Gen2 are exclusive to Fabric and the successor to Gen1, expanding functionality in different ways. They still overlap but have some key distinctions outlined below:

- Authoring experience. Gen1 and Gen2 both use the Power Query Online experience in the Power BI Service, but Gen2 has autosave (including drafts) and background validation.

- Output destination. Gen1 by default persists output in internal storage provided by Power BI, or ADLS Gen2 storage account provided by you. Gen2 can output a query to a variety of destinations: Azure SQL database table, Azure Data Explorer (Kusto) table, ADLS Gen2 file, Fabric Lakehouse delta table, Fabric Lakehouse file, Fabric Warehouse table, Fabric KQL database table, Fabric SQL database table and SharePoint file. Destinations are configured per query, so a single Gen2 dataflow can load different queries to different destinations.

- Output shape. Gen1 publishes entities in managed storage intended to be consumed as tables via the dataflow/CDM connectors, not as user-designed files. Gen2 can publish tables or files, where “files” are a first-class destination for downstream file-based workflows.

- Licensing. Gen1 is available in Pro workspaces. Some important features of Gen1 dataflows like the Enhanced Compute Engine, DirectQuery, incremental refresh and computed/linked entities are only available to Fabric, Premium or PPU capacity workspaces. Gen2 requires the workspace to be on a Fabric or Fabric trial capacity.

- Execution and compute. Gen1 dataflows in Pro workspaces run on the shared Power BI capacity with tighter refresh limits. If Gen1 is in a Fabric, Premium or PPU capacity workspace, the Enhanced Compute Engine (ECE) can be enabled after which features like DirectQuery to that Gen1 dataflow become available. It’s then also possible to re-use queries from existing dataflows by referencing them (linked entities) into new computed entities. Gen2 dataflows run on Fabric SQL compute engines backed by the Fabric capacity and use automatically created staging assets like lakehouses and warehouses for data access and storage. These staging assets exist in the workspace and Microsoft advises not to access or modify them directly.

- Incremental refresh. Gen1’s incremental refresh mechanism is partition-based. Partitions are reloaded selectively and can get merged opportunistically over time as they move out of the incremental range, e.g. months are merged into quarters, to improve storage and query performance. Gen2 incremental refresh works with fixed single-unit buckets (i.e. days or weeks or months, etc.) and uses a replace approach in the destination for the buckets of data it processes (i.e. delete and insert for that range). It’s configured directly in the Gen2 editor and has explicit limits (e.g. number of buckets).

- Integration with other Fabric assets. Gen1’s default Power BI storage can be consumed through the Power Query dataflows connector available in semantic models and dataflows. Other Fabric assets can only use Gen1 dataflows if you brought your own ADLS Gen2 storage. For Gen2 dataflows, other Fabric assets are first-class citizens: storage can be output to the variety of destinations described earlier and pipelines can orchestrate runs of Gen2 dataflows.

- DevOps and lifecycle. Gen1’s are supported in Fabric deployment pipelines (with some limitations) but not by workspace Git integration. For CI/CD in practice, that means you’d need workarounds like exporting and importing Gen1 dataflow definitions through the REST API. Gen2 dataflows are fully supported by Fabric deployment pipelines and workspace Git integration.

- Schema changes. Gen1 stores the data in a dataflow-managed format, so the schema is whatever it is at refresh time. Changing the schema drops all data and always requires a full reload. Gen2, in contrast, can output to destinations where schema changes must be handled: either strictly (fixed schema and fail if it doesn’t match) or flexibly (dynamic/managed: the destination schema is adjusted to match).

- Monitoring. Gen1 has refresh history per dataflow in the Power BI Service user interface. Gen2’s refreshes are available in the ‘Monitoring Hub’ interface with more run metadata and activity-level details.

- Permissions. Gen1 can be consumed by workspace Viewers, without support for row-level security. Gen2 can only be consumed by workspace Contributors and up; Viewer isn’t supported. Row-level security is supported through the destination.

- Gateway constraints. Both Gen1 and Gen2 dataflows can only use one gateway per dataflow. Gen2 currently has some known gateway outbound port 1433 issues for destinations.

- Platform limits. Gen1 on shared capacity has stricter limits (e.g. refresh time-outs at 2 hours per table and 3 hours per dataflow) and useful features like incremental refresh are gated behind capacity requirement. The limits for Gen2 are more specific and related to Data Factory, like permission and tenancy constraints.

- Copilot and AI integration. There is no AI integration or Copilot support for Gen1 Dataflows. Gen2 features Copilot support for creating queries and sample data with natural language prompts, if you’ve set up Copilot in Fabric with the appropriate subscriptions.

These differences reveal a clear general direction: Gen2 have superseded Gen1 dataflows in most cases. Microsoft’s development efforts are clearly on Gen2, so the feature gap is expected to widen. Gen1 can still be a pragmatic choice if you primarily work with Pro/shared workspaces and/or are not ready yet for Fabric adoption. The lack of advanced features like incremental refresh and stricter refresh limits in Pro/shared workspaces can bite, however.

Dataflows vs Power Query in import semantic models

Power Query inside an import semantic model is often the fastest way to get started, but scales poorly when you have multiple models, multiple teams, or repeated data transformation that should be consistent across the tenant/organization.

Dataflows are typically better when you want:

- Re-usable transformation across models. If the same transformation logic is duplicated across multiple models, you have the overhead of managing it across models and the risk of drift between models. Centralizing the logic in a dataflow reduces the overhead and negates the drift risk.

- Controlled source access. Instead of every semantic model or user having direct access to the source system, a dataflow can become the managed ingestion and transformation layer. This is especially useful when only specific data from a source should be consumed.

- Separation of refresh. Dataflows refresh independently from semantic models. They can run on their own schedule and won’t cause downstream model refreshes to fail if they fail. That also means that there are two refresh layers to coordinate: the dataflow(s), and then the semantic model.

- Multi-consumer support. Power Query in a semantic model can only serve that model. A Gen2 dataflow can land transformed tables in a lakehouse or warehouse and then feed semantic models, notebooks, SQL-based consumers, etc.

Embedding Power Query in semantic models is often still the right choice if:

- Transformations specific to the model can’t be pushed upstream and are unlikely to be re-used by other models.

- You want one refresh (the semantic model one) to reason and worry about.

WARNING

The right tool for the job

Dataflows are designed for low-code ingestion and transformation. They can persist results, but they don’t replace the governance patterns you typically apply in a warehouse like stable schemas, explicit modeling, lineage, and controlled change management. If you notice your dataflows becoming the core system that everything depends on, that’s usually a sign to introduce a lakehouse/warehouse layer and simplify the dataflows.

Dataflows vs Fabric notebooks

Notebooks and dataflows overlap because both can ingest and transform data. The difference is not “what can be done”, but who the primary user is and how much engineering overhead you’re willing to take on.

Dataflows are typically better when you want:

- You want to optimize for simplicity. This is most suitable for decentralized or self-service scenarios where non-technical teams take ownership of ETL.

- Low-code transformations with Power Query M in a graphical user interface. Power BI developers often already have the Power Query skill so can get started with dataflows quickly.

- A simple way to publish re-usable tables in different formats. Gen2 can land tables or files to supported destinations per query.

- A lighter BI ingestion operating model, in an environment where engineering-heavy transformations are rare and Power Query M is well adopted.

Notebooks are generally a better choice when:

- You want to optimize for cost. Notebooks in Fabric are generally considered more cost-effective and performant than alternatives for many scenarios (although this is not ubiquitous).

- You need engineering-grade flexibility or observability, like custom libraries, tests, complex logic and structured logging. This is typically more suitable for centralized scenarios where BI or IT teams own ETL processes, or where decentralized teams are more comfortable working with code.

- You want a code-first lifecycle. Notebooks are typically written in PySpark, Python, or T-SQL. This is particularly interesting when you use LLMs and coding agents like Claude Code to facilitate notebook development. Data Wrangler lowers the “barrier of entry” to code by providing a GUI to pick code snippets for common transformations, and integration of Copilot to assist with writing code.

- Workloads are often heavy or large-scale.

Getting started with dataflows

When starting out with dataflows, the first decision is whether to create a Gen1 or Gen2 Dataflow:

- If you’re not on Fabric capacity, Gen1 is the only choice you have.

- If you do have access to a Fabric capacity, then Gen2 is on the table. You don’t automatically have to go for Gen2, however. If semantic models will be the only consumers of the dataflow, and you don’t need to land the data in a lakehouse/warehouse/SharePoint/etc., Gen1 can be a pragmatic on-ramp.

- If the dataflow will be used beyond semantic models or the data must be landed in a lakehouse/warehouse/SharePoint/etc., Gen2 is the only dataflow option.

Once you’ve picked a generation, the next choices are mostly about scope, contracts and operations:

- Keep the scope re-usable, not model-specific. Dataflows are most valuable when they produce curated, broadly useful tables. If you find yourself adding transformations that only apply to one semantic model, it’s a sign that this logic applies in that semantic model’s Power Query instead.

- Treat the output schema as a contract. Whether you’re publishing to Gen1’s managed storage or Gen2’s destinations (lakehouse, SharePoint, etc.), downstream consumers will depend on specific column names, types, and meanings. If any of these change without prior notice, refreshes will fail and users can be impacted. When frequent changes are expected, plan for them up front (especially in Gen2 destinations where you can choose between strict or flexible schema handling).

- Be deliberate about refresh orchestration. Moving transformations into a dataflow introduces another refresh layer. This separation can be a strength (independent schedules, isolation of failures), but it also means having to make sure dataflows have refreshed successfully before downstream consumers’ refreshes.

- Choose the destination based on who needs the data. In Gen2, the output destination is part of the design. Pick the destination that best fits the consumption patterns:

- Use lakehouse or warehouse tables when you want a durable curated layer that can be consumed by multiple semantic models, notebooks, or SQL-based consumers.

- Use files when the downstream workflow is file-based (e.g. exports for external sharing, interoperability with Spark).

- Have a rule for when to switch to notebooks. Dataflows are good for low-code transformations and simple ETL. If transformations become engineering-heavy (e.g. complex algorithms, large joins, etc.), notebooks are usually the better long-term choice.

- Name and document dataflows like they’re a shared asset. Dataflows are high-dependency items once re-used. Use clear naming, short descriptions and ownership conventions so people can (securely) discover and adopt them.

Start small, optimize for re-use, and avoid turning dataflows into an accidental data warehouse.

Further recommended reading

In conclusion

Dataflows are best viewed as a re-usable low-code transformation layer that sits between sources and semantic models. Gen1 remains a pragmatic choice for Pro-centric Power BI scenarios while Gen2 is the forward-looking choice on Fabric capacity, especially when you want broader destinations, tighter integration and a more automation-friendly lifecycle. If transformations become engineering-heavy or cost/performance is the primary concern, notebooks are often the better long-term home.